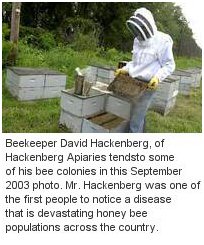

Disease Killing Bees

One day last November, David Hackenberg, of Lewisburg, went out to check on some of his honey bees and found the 400 hives completely empty. There was no sign of

the bees, dead or alive. There was no sign that a predator had been there, and no other bugs had moved in.

Something was horribly wrong.

"They'd all vanished," he said, speaking on the phone from Florida, where he spends the winter so that his

bees can pollinate fruit orchards all year-long. "This is unheard of."

It was one of the first hints of the arrival of a disease that has devastated honey bee populations across the U.S.

Mr. Hackenberg gathered material from the hives and took it to researchers at Penn State.

The disease has since been described as Colony Collapse Disorder, but what causes it is still not entirely

understood.

"During the last three months of 2006, we began to receive reports from commercial beekeepers of

an alarming number of honey bee colonies dying in the eastern United States," said Maryann Frazier, apiculture

extension associate in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences in a written statement distributed by the

university. "Since the beginning of the year, beekeepers from all over the country have been reporting

unprecedented losses."

Dennis vanEngelsdorp, acting state apiarist with the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, said that the

causes of the disease could include "mites and associated diseases, some unknown pathogenic disease and

pesticide contamination or poisoning."

Initial studies of dying colonies revealed a large number of disease organisms present, with no one disease

being identified as the culprit, Mr. vanEngelsdorp said in the Penn State press release. Ongoing case studies

and surveys of beekeepers experiencing Colony Collapse Disorder have found a few common management factors, but

no common environmental agents or chemicals have been identified. The devastation caused by the disease is

unlike anything he's seen in four decades of tending bees, Mr. Hackenberg said.

Before it hit, the Hackenbergs had close to 3,000 hives. They're down to fewer than 1,000 now.

"I don't mind telling you, there were a lot of nights that I was out there with tears in my eyes," he said. "This is my livelihood."

But the Hackenbergs are determined to survive the disaster, he said, adding that he feels like the worst might be behind them in Florida.

"We'll make it," he said.

Others might not be so lucky.

He described how one beekeeper he knows took three truckloads of bees across country - a task that costs $50,000

- with the expectation of making $150,000 in revenue on the trip.

Only one truckload of bees survived the journey.

"He'll be lucky to break even," Mr. Hackenberg said. "And he told me, this may be the one that puts me out of business."

Another farmer in western Pennsylvania had 1,200 hives before the disease hit. Now he's got 80, Mr. Hackenberg said.

This latest loss of colonies could seriously affect the production of several important crops that rely on pollination services

provided by commercial beekeepers, researchers said.

"(Pennsylvania's) $45 million apple crop - the fourth largest in the country - is completely dependent on

insects for pollination, and 90 percent of that pollination comes from honey bees," Ms. Frazier said. "So the

value of honey bee pollination to apples is about $40 million."

In total, honey bee pollination contributes about $55 million to the value of crops in the state. Besides

apples, crops that depend at least in part on honey bee pollination include peaches, soybeans, pears, pumpkins,

cucumbers, cherries, raspberries, blackberries and strawberries.

And while beekeepers in warm weather states already know how the disease has affected their colonies, how it

will affect those in the North won't be clear until the spring. In cold weather, bees survive by huddling

together inside their hives. The president of the Beekeepers of the Susquehanna Valley William Blodgett, of

Danville, said that beekeepers, like him, with smaller numbers of bee that don't travel much, are presumably

less likely to get hit by the disease than larger commercial operations.

Anyone who keeps bees is certainly aware of the disease, but it hasn't caused any widespread panic among the

23 members of the local beekeepers' association, he said.

"I don't think it will affect me. But bees normally get this (disease) when they are in a confined space, and

they've been together for the winter," Mr. Blodgett said. "Who knows? We may peek into our hives at the end of

the month and find them empty," he said.

The impact on smaller beekeeping operations will determine, in part, how much disruption the disease causes to

the kind of small fruit farms commonly found in central Pennsylvania.

"The little guy who relies on the guy down the road to provide him bees, could be in real trouble if the guy

down the road doesn't have any bees," Mr. Hackenberg said.

The economic implications of the problem may be all the more pressing because even before the disease hit, the

number of beekeepers had been dwindling.

"This has become a highly significant yet poorly understood problem that threatens the pollination industry and

the production of commercial honey in the United States," Ms. Frazier said. "Because the number of managed honey

bee colonies is less than half of what it was 25 years ago, states such as Pennsylvania can ill afford these

heavy losses."

On the bright side, there are so few beekeepers available that Mr. Hackenberg said it's unlikely that any states

will try to ban apiaries that have already suffered losses in an attempt to stop the spread of the disease.

"They can't," he said. "There aren't enough of us left."